Coinbase's €21.5M AML Fine: You Can’t Automate Accountability

What every GC can learn from Coinbase’s €21.5M AML fine (a.k.a. How to lose €176 Billion worth of transactions in plain sight)

👋 Get the latest legal insights, best practices, and legal breakdowns. I cover everything tech companies need to know about legal stuff.

So let’s start with the headline: The Central Bank of Ireland just fined Coinbase €21.5 million for anti-money-laundering (AML) failures last week.

The reason? A “coding error” in their transaction-monitoring system that left billions of euros in transactions unchecked…for three years.

However, this is not a crypto story. This is a compliance systems story. Because if you replace “AML” with “privacy,” “AI,” “export,” or “sanctions,” every GC in tech is one log-rotation away from starring in their own version of this movie.

The Backstory (and Why It Hurts)

Between 2020 and 2023, Coinbase Europe’s automated AML engine had a logic flaw that effectively excluded a large portion of transactions from monitoring.

We’re talking €176 billion in transactions that skipped review.

When they fixed it, they self-reported and back-reviewed the data; discovering 2,700 suspicious transactions that should’ve been escalated years earlier.

The Central Bank’s tone? Disbelief mixed with irritation. Their statement could be summarized as: “Automation is not a substitute for oversight.”

Translation for GCs: “You can outsource the work, not the accountability.”

The Lesson: “Tech Glitch” Is Not a Defense

In-house, we love to blame bugs. I’ve seen it a hundred times: a policy says “continuous monitoring,” IT says “the script runs daily,” and Legal assumes it’s all good.

Until it’s not.

The Coinbase case is a brutal reminder that regulators don’t care whether your failure came from negligence or code drift.

They care that you didn’t catch it sooner.

When compliance automation fails, the legal question quickly becomes:

Did you know it failed?

Should you have known?

And what governance model existed to find out?

If your only line of defense is “we trusted the dashboard,” congratulations, you’re one bad SQL query away from a headline.

What I’ve Seen (and You Probably Have Too)

I once joined a call where IT swore their monitoring system was “fully automated.”

I asked how they validated it.

They said, “The dashboard’s green.”

We pulled the data. The dashboard was green because the error handler failed silently for 47 days.

Our “continuous monitoring” was, in fact, continuously broken.

Lesson learned: Green doesn’t mean good. It means nobody’s checking.

What Coinbase Missed…and You Might Too

You don’t need to run a crypto exchange to fall into this trap. Coinbase’s failure could just as easily happen in your privacy, cybersecurity, sanctions, or AI governance stack.

Here’s what likely went wrong under the hood:

Model or rules drift: Someone tweaked the monitoring logic or schema, and certain transaction types fell outside the scope.

No change-control testing: Updates went straight to prod without regression checks.

No control assurance: Compliance relied on output summaries, not raw validation.

Poor board reporting: KPIs showed “transactions reviewed,” not “transactions unmonitored.”

No auto-alert for volume anomalies: A gap that big should’ve tripped alarms for data integrity.

Every one of these is common. None of them is “crypto-specific.”

Replace “transactions” with “data transfers,” “vendor queries,” or “AI model access logs,” and you’re staring at your own risk register.

What This Means for GCs

This case is a five-alarm fire for governance of automation.

We’ve spent years telling our companies to automate compliance.

Now we have to explain to our boards that automation can fail just as spectacularly, and much more quietly, than people.

Your new role: Be the person who asks “who’s checking the checker?”

That means:

Embedding control assurance into every automated process.

Setting a cadence for quarterly back-reviews (yes, even when “nothing’s wrong.”)

Building cross-functional ownership: compliance writes the rules, IT enforces them, Legal audits the output.

And documenting all of it, because “we thought it worked” isn’t going to cut it in a regulator meeting.

The GC’s “Monitoring Failure Playbook”

Here’s how to prevent your automation from turning into your next enforcement action:

Define control ownership clearly. Who owns the rule logic? Who signs off when it changes? I’ve seen companies where “everyone” owns it… which means no one does.

Establish pre-deployment testing. Every change to your monitoring logic should go through a test environment with seeded alerts. If your team rolls updates directly into production, you’re inviting ghosts into your data.

Implement drift detection. Code and data models evolve. Controls should alert when coverage drops or field mappings change.

Set a back-review schedule. Pick a period (monthly, quarterly) and re-run historic data to catch missed flags. It’s boring, but so is being fined €21.5 million.

Create escalation and reporting triggers. If anomalies spike or coverage dips, Legal should see it within 24 hours, not after the next quarterly ops review.

Maintain a “hotline for robots.” That is, a process for employees to report suspected control failures. Someone always notices something weird before the system does.

Make your dashboards human-readable. No one on the board cares about API call rates. They care about coverage percentage, missed alerts, and financial exposure.

Do a post-mortem before the regulator does. If something breaks, investigate immediately, document it, and fix it fast. Regulators will forgive an error. They won’t forgive silence.

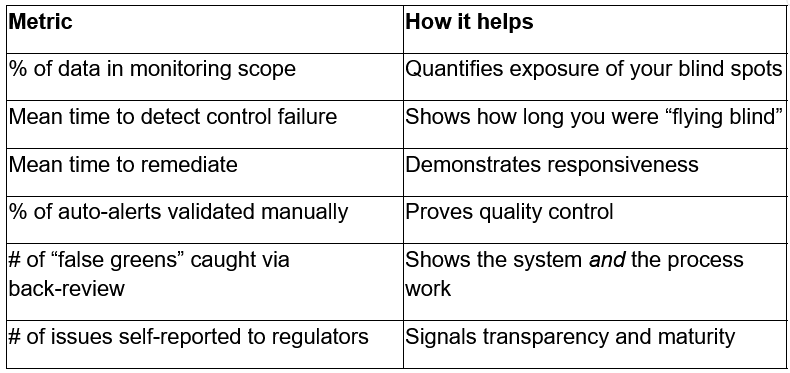

The Metrics That Actually Matter

If your board deck still shows “# of alerts generated,” you should change it.

Here are metrics that help tell a story:

The Regulatory Subtext: Automation ≠ Accountability

The Coinbase decision is a turning point in how regulators view automation.

The subtext was clear: “You built the system. You’re responsible for knowing when it breaks.”

It’s the same logic we’re starting to see in AI governance and data security enforcement. If your algorithm or automation makes a compliance decision, the company owns the outcome—not the vendor, not the code, not the intern who pushed the update.

I expect to see more of this logic bleed into other enforcement areas:

Privacy DPIAs that rely on automated tagging tools.

Sanctions screening done by third-party models.

HR systems auto-processing cross-border data.

If any of those fail quietly for months, expect regulators to say, “We’ve seen this movie before…and it ends in fines.”

The GC’s Role in “Invisible Failures”

To be honest: most GCs are not auditing code. But your job isn’t to be the engineer, it’s to ensure governance exists.

You don’t need to know how the regex works. You just need to know that someone’s checking that it still works.

Ask these five questions in every automation-heavy process review:

What triggers tell us a control has stopped working?

Who’s responsible for detecting those triggers?

When was the last time we manually validated the output?

How is this risk reported up to me or the board?

What’s our plan if it fails silently for a month?

If you don’t get a crisp answer, assume there isn’t one.

“But We Self-Reported!” The False Comfort

Coinbase did the right thing by self-reporting once they found the bug.

But self-reporting doesn’t erase three years of exposure. Regulators treat it as mitigation, not absolution.

I’ve seen this play out in other sectors:

A fintech self-reported a failed sanctions screen. The regulator still fined them, but cut it in half.

A SaaS company self-disclosed a data-retention gap. They escaped fines but were stuck under a 2-year compliance monitor.

So yes, disclose. But don’t expect a gold star.

The Real Cost

€21.5 million sounds painful, but the real cost wasn’t the fine, rather it was the remediation. Coinbase reportedly had to:

Reprocess millions of transactions retroactively

File 2,700 Suspicious Transaction Reports (STRs)

Update internal monitoring logic and documentation

Deal with months of regulator meetings

Add legal fees, consulting, reputational damage, and lost time, and the true cost likely hit eight figures.

And that’s before you count the operational drag of fixing controls under a microscope.

For every company that says, “we’ll cross that bridge when we get audited,” remember: by the time you’re crossing it, it’s already on fire.

What Every GC Should Do This Quarter

If you want a quick sanity check on whether your automation might be hiding a time bomb, start here:

Ask your IT or compliance team to show you how they know their controls are working.

Review any automated process that touches regulators, customers, or money.

Add “control drift review” as a standing agenda item for your risk committee.

Make sure your board reports focus on risk coverage, not just activity counts.

And most importantly: establish a “we’d rather find it than hide it” culture.

You can’t fix what nobody’s looking for.

Final Thought: The Automation Illusion

Automation doesn’t remove human error, it industrializes it.

When something goes wrong in a manual process, you get a few bad entries.

When something goes wrong in an automated one, you get three years and €176 billion worth of “oops.”

Coinbase’s fine is a good wake-up call.

We’ve built legal and compliance programs on automation, AI, and dashboards that say “all clear.”

Now it’s time to add a new line to your risk matrix: Silent system failure: detected only when the regulator calls.

Spot on. Imagine this "logic flaw" in an AI system deciding healthcare acess. A different kind of log-rotation nightmare.